Adventures

Remembering Rector’s Restaurant in NYC & Micka's Market in Michigan

Dec 13, 2025

l. to r.: Kellen Rector inside Grand Central Station, New York City; pizza from L'industrie Pizzeria, New York City. Cover photo credit King’s Views of New York City, 1903 (copyright expired).

Whenever I travel through New York on my way back home to Florida for break, it often begins the same way. I take Vanderbilt's train route from the Culinary Institute of America into Grand Central on my way to JFK. I make a full day of it in the City. I walk, observe, and always choose a couple of restaurants to try. Places that help me better understand New York’s food culture, past and present.

ON A SIDE NOTE: Chef Kellen Rector is not related to Charles or George Rector. The connection is purely a shared last name, though the culinary legacy itself is deeply inspiring.

New York City has always been a place where food, culture, and spectacle collide. Long before Times Square became the neon crossroads we know today, one restaurant helped define Broadway dining at the turn of the 20th century: Rector’s Restaurant.

In 1899, restaurateur Charles Rector joined the fray, opening a restaurant on West 44th Street on a dreary commercial intersection named Long Acre Square. As noted by The American Menu, this moment marked the beginning of one of New York’s most talked‑about dining rooms at the dawn of the Gilded Age.

Charles Rector was already an accomplished restaurateur when he brought his vision to New York. Rector’s quickly became known not only for its ambitious menu and polished service, but for its sheer theatricality. Dining at Rector’s was as much about being seen as it was about eating well, a perfect match for the rapidly evolving Broadway scene.

Charles Rector understood that great restaurants were built by great people. According to The American Menu, he recruited culinary talent from the most respected kitchens in New York:

“Rector recruited culinary talent from the kitchens of Delmonico’s, Sherry’s, and the Waldorf‑Astoria where he found his head chef Emil Hederer, convincing him to leave the hotel ‘by dangling $7000 a year under his capable nose.’”— The American Menu

Not surprisingly, the menus at Rector’s initially looked much the same as those at the Waldorf‑Astoria — showcasing classic French preparations, luxurious ingredients, and elaborate multi‑course offerings that defined fine dining at the time.

By 1902, Charles began preparing the next chapter of the restaurant’s story.

“Charles Rector’s 24‑year‑old son George was put in charge of the dining room in 1902, having recently returned from France where he had been sent to learn about food and wine.”— The American Menu

This transition marked a pivotal moment, blending Charles Rector’s entrepreneurial drive with George Rector’s European culinary training.

Under George Rector’s leadership, the dining room became a showcase of French‑influenced cuisine, refined service, and social energy. Rector’s drew theatergoers, financiers, and socialites, cementing its place as one of Broadway’s most fashionable destinations.

Today, Times Square pulses with LED screens, crowds, and constant motion. Standing here now, it’s hard to imagine the same ground occupied by a grand dining room where chandeliers glowed, tuxedoed waiters moved with precision, and Broadway’s elite lingered late into the night. This modern photo anchors the story, a visual reminder of how dramatically the city has changed, and how deeply its culinary past is layered beneath the pavement.

Photographs from The American Menu reveal a restaurant designed to impress from the street inward. The exterior was crowned with massive electric signage spelling RECTOR’S, a beacon of modernity at the dawn of the electric age. Oversized parapets, glowing letters, and architectural flourishes ensured the building stood out amid the crowded Broadway streetscape.

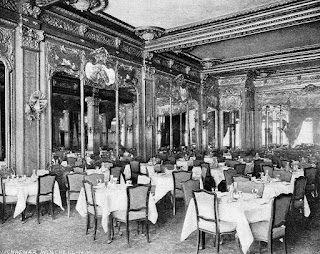

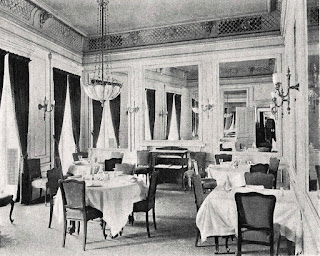

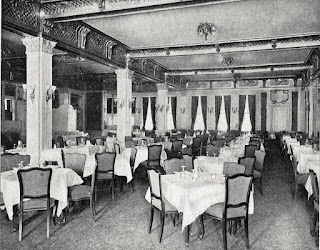

Inside, Rector’s was equally dramatic. Lavish dining rooms featured ornate décor, mirrors, rich woodwork, and elegant table settings. The atmosphere balanced formality with excitement, a place where fine dining met Broadway nightlife, and where lingering over dinner was part of the experience.

The Main Dining Room. The American Menu.

Rector’s menus evolved over the years, and the surviving examples show just how intentional their design was. Visit The American Menu for more information on the menus. Early menu covers echoed the elegance of the era, often featuring refined typography, decorative borders, and subtle illustrations that mirrored the restaurant’s upscale positioning.

As Rector’s grew in reputation, menu covers became bolder and more expressive reflecting both changing design trends and the restaurant’s growing confidence. Inside, diners found extensive selections: oysters, terrapin, elaborate meat and game dishes, and signature lobster preparations that would later become synonymous with George Rector’s culinary legacy.

Rector’s was famous not only for food, but for its atmosphere and indulgences — including its own branded cigars.

“The plate below indicates that Rector’s had its own brand of cigars. Customers were forever slipping plates, silverware, and other knickknacks into their pockets. If they asked, the management gave them these items free of charge. If not, the cost of the pilfered souvenirs was quietly added to the bill. Few menus were saved.”— The American Menu

This detail offers a vivid glimpse into the dining culture of the time, when excess, luxury, and a sense of playful indulgence were part of the experience. The cigar plate is from my own collection of restaurant memoribilia.

One of the most meaningful links I have to this story is a signed copy of Home on the Range by George Rector. I’ll be adding recipes from the book to Kellen’s Kitchen.

The signed cookbook was a gift from my grandmother, Carolyn Rector, who discovered it, along with a Rector’s cigar plate, in an antique store in Highlands, North Carolina. Holding it feels like holding a piece of American culinary history, a tangible reminder of an era when restaurants like Rector’s defined elegance and ambition.

Home on the Range with George Rector. Rector Publishing Company 1939. Kellen Rector private collection, 2025.

While Charles Rector was passing the dining room torch to George in New York, my own great‑great‑grandparents, Joseph and Katrina Micka, were beginning their American story, landing at Ellis Island from Czechoslovakia. These parallel timelines reflect the broader immigrant and entrepreneurial spirit that shaped America’s food culture.

Left: Katrina Micka, Charles Micka, Joseph Micka, Richard Micka and Tom Micka., 1946. Kellen Rector private collection.

Right: The Generations Continue. Thomas Micka, II, Elizabeth Micka, Eva, Rose and Thomas Micka, III.

Their son, Charles Micka and my great grandpa, carried that spirit forward when he opened Micka’s Market in Monroe, Michigan in 1935. The meat market and grocery store became a cornerstone of the local community, known for quality ingredients and personal service.

Charles Micka sourced his spices from a New York City seasoning supplier named Aulva, quietly linking a small Midwestern market back to the same city that defined luxury dining through places like Rector’s.

After graduating Western Michigan and leaving as a Lieutenant in the Army, my grandfather, Tom Micka, purchased the family business from my great grandfather, continuing the tradition of craftsmanship of making homemade smoked sausages, butchering meats, sourcing for the market and customers, and respect for food, values that still guide my own approach in the kitchen today. In upcoming posts, I’ll be sharing more about Micka’s Market, its family recipes bridging Broadway’s gilded dining rooms with Midwest markets and modern kitchens.

Rector’s Restaurant no longer stands, but its influence remains. Like so many places that once defined their communities, its disappearance reminds us how fragile culinary landmarks can be.

The same is true closer to home. Micka’s Market, opened in Monroe, Michigan, in 1935 by my great‑grandpa Charles Micka and later run by my grandfather Tom Micka, no longer stands either. Yet its legacy lives on through family recipes, stories, and the values passed down, respect for ingredients, thoughtful sourcing, and food as a connector.

Remembering Rector’s isn’t about nostalgia alone. It’s about honoring places from grand Broadway dining rooms to neighborhood markets that shaped how we cook, eat, and gather, and allowing those foundations to continue inspiring chefs, diners, and storytellers today.

Additional historical reference:

Fresh Smoked Sausage Items and Other Various Recipes Used at Micka's Market

By Charles J. Micka

Private recipe collection, December 1989

“The Lost Rector’s Restaurant – 1508–1510 Broadway”

Monday, January 16, 2023

THE AMERICAN MENU

Saturday, August 22, 2015

Rector’s — New York City, 1899–1919